Two years ago, I wrote an article about Thimbleweed Park, the Kickstarter-funded adventure game project from Lucasfilm Games legends Ron Gilbert, Gary Winnick and David Fox – and then sadly never got around to mention it again. In the meantime, the game has been successfully developed – which was extensively documented on their website – and finally released this Spring. Ironically, I was not able to play the game in its PC version because, despite its retro look, the engine has some requirements in the graphics department that made it impossible to run on my aging computers! But recently, more than half a year after the initial release, the Android port has finally been released and to my delight it runs on my tablet and phone. Time to go back to 1987, which is very appropriate since 2017 is the 30th Anniversary of Lucasfilm Games’ first point-and-click adventure Maniac Mansion!

Two years ago, I wrote an article about Thimbleweed Park, the Kickstarter-funded adventure game project from Lucasfilm Games legends Ron Gilbert, Gary Winnick and David Fox – and then sadly never got around to mention it again. In the meantime, the game has been successfully developed – which was extensively documented on their website – and finally released this Spring. Ironically, I was not able to play the game in its PC version because, despite its retro look, the engine has some requirements in the graphics department that made it impossible to run on my aging computers! But recently, more than half a year after the initial release, the Android port has finally been released and to my delight it runs on my tablet and phone. Time to go back to 1987, which is very appropriate since 2017 is the 30th Anniversary of Lucasfilm Games’ first point-and-click adventure Maniac Mansion!

Thimbleweed Park really feels like a proper adventure game from the golden era of the late 1980s or early 1990s, and it’s not just the pixel art or the user interface. Ron Gilbert, Gary Winnick and David Fox also took the opportunity to tell a great story, something that had always been a part of the adventure genre and got lost somewhere in the last decade or two. Thimbleweed Park’s plot feels like a well-stirred mix of Maniac Mansion, Zak McKracken and Monkey Island with a bit of The X-Files thrown in as special seasoning – and despite the familiar atmosphere, it’s a completely new original tale that starts out as a simple murder mystery but soon develops into something much bigger. The true scope of the game only reveals itself after playing quite a while, but that’s what makes Thimbleweed Park so fascinating.

Thimbleweed Park really feels like a proper adventure game from the golden era of the late 1980s or early 1990s, and it’s not just the pixel art or the user interface. Ron Gilbert, Gary Winnick and David Fox also took the opportunity to tell a great story, something that had always been a part of the adventure genre and got lost somewhere in the last decade or two. Thimbleweed Park’s plot feels like a well-stirred mix of Maniac Mansion, Zak McKracken and Monkey Island with a bit of The X-Files thrown in as special seasoning – and despite the familiar atmosphere, it’s a completely new original tale that starts out as a simple murder mystery but soon develops into something much bigger. The true scope of the game only reveals itself after playing quite a while, but that’s what makes Thimbleweed Park so fascinating.

The game is, however, not a laugh-out-loud comedy, but goes for a more sarcastic and even cynical tone of humour. Much more in the vein of Maniac Mansion and Zak McKracken than Monkey Island, Thimbleweed Park’s back story is actually a rather serious and sometimes even slightly sad tale involving murder, intrigues, conspiracies and family tragedies. Despite the underlying plot, the game has an atmosphere that is best described as snarky – the characters and plot are treated earnestly and everything feels real and believable to a certain degree, helped by an underlying sense of humour that never lets the game go all too serious.

The game is, however, not a laugh-out-loud comedy, but goes for a more sarcastic and even cynical tone of humour. Much more in the vein of Maniac Mansion and Zak McKracken than Monkey Island, Thimbleweed Park’s back story is actually a rather serious and sometimes even slightly sad tale involving murder, intrigues, conspiracies and family tragedies. Despite the underlying plot, the game has an atmosphere that is best described as snarky – the characters and plot are treated earnestly and everything feels real and believable to a certain degree, helped by an underlying sense of humour that never lets the game go all too serious.

There are also a lot of inside jokes, self-references and multiple instances of breaking the fourth wall – the whole of Thimbleweed Park is actually a love letter to classic adventure games, even with a whole subplot revolving about one of the characters applying for a game developer job at an only thinly disguised LucasArts-esque company. This wonderful nostalgia does not even feel remotely dated, but it might be hard to follow for younger players who have never experienced this era of computer games themselves – although it still makes Thimbleweed Park a perfect homage to the classic adventures of the golden age.

There are also a lot of inside jokes, self-references and multiple instances of breaking the fourth wall – the whole of Thimbleweed Park is actually a love letter to classic adventure games, even with a whole subplot revolving about one of the characters applying for a game developer job at an only thinly disguised LucasArts-esque company. This wonderful nostalgia does not even feel remotely dated, but it might be hard to follow for younger players who have never experienced this era of computer games themselves – although it still makes Thimbleweed Park a perfect homage to the classic adventures of the golden age.

Together with the huge story go the well-developed characters whose backgrounds are fleshed out with the help of flashbacks, which are not just cutscenes but actually part of the playable game. Almost all of them have a big story to tell about themselves through the plot. And there’s lots and lots of dialogue – this is a very talkative game, probably primarily thanks to the fact that game writer Lauren Davidson had joined the team to work on the story and dialogue, so that Ron Gilbert, David Fox and Jenn Sandercock, another “outside” recruit, could concentrate on the programming and the game logic.

Together with the huge story go the well-developed characters whose backgrounds are fleshed out with the help of flashbacks, which are not just cutscenes but actually part of the playable game. Almost all of them have a big story to tell about themselves through the plot. And there’s lots and lots of dialogue – this is a very talkative game, probably primarily thanks to the fact that game writer Lauren Davidson had joined the team to work on the story and dialogue, so that Ron Gilbert, David Fox and Jenn Sandercock, another “outside” recruit, could concentrate on the programming and the game logic.

Thimbleweed Park’s puzzles are in the true Lucasfilm Games tradition and are very tightly interwoven with the story. Most of them involve the usual searching for items, but it’s never one senseless quest after another that have nothing to do with the plot – the puzzles are the plot here, just like it should be in a proper adventure game. In large parts of the game, the player controls five characters simultaneously, but the puzzles are never so illogical or complex that they are unsolvable. Players who are familiar with Lucasfilm adventures do have a distinct advantage, but for the uninitiated Thimbleweed Park also provides a light mode with fever puzzles like Monkey Island 2 did. It’s also impossible to run into dead ends or die in this game – something the inside jokes make a great point of – although there are even ghosts among the characters.

Thimbleweed Park’s puzzles are in the true Lucasfilm Games tradition and are very tightly interwoven with the story. Most of them involve the usual searching for items, but it’s never one senseless quest after another that have nothing to do with the plot – the puzzles are the plot here, just like it should be in a proper adventure game. In large parts of the game, the player controls five characters simultaneously, but the puzzles are never so illogical or complex that they are unsolvable. Players who are familiar with Lucasfilm adventures do have a distinct advantage, but for the uninitiated Thimbleweed Park also provides a light mode with fever puzzles like Monkey Island 2 did. It’s also impossible to run into dead ends or die in this game – something the inside jokes make a great point of – although there are even ghosts among the characters.

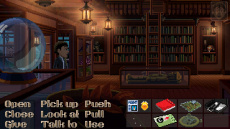

Despite its hertiage, Thimbleweed Park does not use Scumm as a scripting language – instead Ron Gilbert adapted an engine he had written himself earlier for the game and paired it with the relatively new language Squirrel. But what happens under the hood does not really have to concern the player at all – only the outwards appearance counts and for this, Thimbleweed Park literally goes back to the roots. The classic verb-and-inventory interface, introduced by Lucasfilm Games in 1987 and then abolished again in 1993, makes a sensible comeback here, turning the game in to a true point-and-click adventure once again. The nine-verb-interface sits next to the familiar graphical inventory that was also made popular by LucasArts starting with Monkey Island 2, so it doesn’t get any more classical than this. Going completely back to 1987 with a text-only interface below the graphics would have been a bit too much, but Thimbleweed Park uses the best of both worlds here in a solid compromise.

Despite its hertiage, Thimbleweed Park does not use Scumm as a scripting language – instead Ron Gilbert adapted an engine he had written himself earlier for the game and paired it with the relatively new language Squirrel. But what happens under the hood does not really have to concern the player at all – only the outwards appearance counts and for this, Thimbleweed Park literally goes back to the roots. The classic verb-and-inventory interface, introduced by Lucasfilm Games in 1987 and then abolished again in 1993, makes a sensible comeback here, turning the game in to a true point-and-click adventure once again. The nine-verb-interface sits next to the familiar graphical inventory that was also made popular by LucasArts starting with Monkey Island 2, so it doesn’t get any more classical than this. Going completely back to 1987 with a text-only interface below the graphics would have been a bit too much, but Thimbleweed Park uses the best of both worlds here in a solid compromise.

The graphics are a collaboration between Gary Winnick, Mark Ferrari – another LucasArts legend brought in during development – and Spanish pixel artist Octavi Navarro – and they are a true sight to behold. The backgrounds are a mix of the original 320×200 pixel and 16 colour style of the early Lucasfilm Adventures up to Monkey Island, but were expanded with the later used 256 colour palette. There are no hand-drawn and scanned graphics like they were used starting on Monkey Island 2 and Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis, instead each and every pixel was lovingly hand-placed on the computer with spectacular results – including artificial dithering on the colours, which is used to amazing results here. The animation is as basic as 25 years ago, but adds a bit of nifty colour cycling, shading and sometimes parallax scrolling. but there are few tricks that would not have been possible on a 256-colour VGA graphics card of the early 1990s. The graphics never feel like they are held back by the limits of the technology, but exactly the opposite – this is true pixel art.

The graphics are a collaboration between Gary Winnick, Mark Ferrari – another LucasArts legend brought in during development – and Spanish pixel artist Octavi Navarro – and they are a true sight to behold. The backgrounds are a mix of the original 320×200 pixel and 16 colour style of the early Lucasfilm Adventures up to Monkey Island, but were expanded with the later used 256 colour palette. There are no hand-drawn and scanned graphics like they were used starting on Monkey Island 2 and Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis, instead each and every pixel was lovingly hand-placed on the computer with spectacular results – including artificial dithering on the colours, which is used to amazing results here. The animation is as basic as 25 years ago, but adds a bit of nifty colour cycling, shading and sometimes parallax scrolling. but there are few tricks that would not have been possible on a 256-colour VGA graphics card of the early 1990s. The graphics never feel like they are held back by the limits of the technology, but exactly the opposite – this is true pixel art.

The character designs are heavily based on Maniac Mansion and Zak McKracken with the slightly enlarged ‘bobble heads’. This unique style vanished after Zak and was never really used at LucasArts again, but here it allows for many brilliant character designs within the resolution pixel limit, which Thimbleweed park almost always adheres to – with one exception: the characters’ pixels shrink when they scale down in perspective, which actually doesn’t look as strange as it could have been. There are more than fifty meticulously designed characters in the game and everyone is brilliantly designed down to the last pixel. Even the animations are mostly limited to the low resolution, which makes the characters even more fun to watch.

The character designs are heavily based on Maniac Mansion and Zak McKracken with the slightly enlarged ‘bobble heads’. This unique style vanished after Zak and was never really used at LucasArts again, but here it allows for many brilliant character designs within the resolution pixel limit, which Thimbleweed park almost always adheres to – with one exception: the characters’ pixels shrink when they scale down in perspective, which actually doesn’t look as strange as it could have been. There are more than fifty meticulously designed characters in the game and everyone is brilliantly designed down to the last pixel. Even the animations are mostly limited to the low resolution, which makes the characters even more fun to watch.

The only parts of Thimbleweed Park that make concessions to modern games are the voice acting, the sound and the music. Surprising for a relatively small Kickstarter-backed project, the producers were able to assemble a fully-fledged voice cast that is mostly comprised not out of amateurs, but professional actors – which you can really hear in the game. Thimbleweed Park does not sound like the first ‘talkies’ of the early 1990s, but more like proper movie dialogue – the actors do a fantastic job here and really bring the characters to life. Especially the main roles of the two agents Rey and Reyes are wonderfully voiced by Nicole Oliver and Javier Lacroix and Elise Kates, Alex Zahara and Ian James Corlett as Dolores, Franklin and Ransome are amazing to listen to as well. The amount of dialogue that is not strictly necessary to listen to in this game is sheer astounding and there is a lot of fun stuff to hear buried deep in the dialogue choices.

The only parts of Thimbleweed Park that make concessions to modern games are the voice acting, the sound and the music. Surprising for a relatively small Kickstarter-backed project, the producers were able to assemble a fully-fledged voice cast that is mostly comprised not out of amateurs, but professional actors – which you can really hear in the game. Thimbleweed Park does not sound like the first ‘talkies’ of the early 1990s, but more like proper movie dialogue – the actors do a fantastic job here and really bring the characters to life. Especially the main roles of the two agents Rey and Reyes are wonderfully voiced by Nicole Oliver and Javier Lacroix and Elise Kates, Alex Zahara and Ian James Corlett as Dolores, Franklin and Ransome are amazing to listen to as well. The amount of dialogue that is not strictly necessary to listen to in this game is sheer astounding and there is a lot of fun stuff to hear buried deep in the dialogue choices.

For the background music and sound, Thimbleweed Park did fortunately not go back all the way to the early 1990s or even late 80s – while MIDI music, Adlib bleeping or chiptunes would have been fun, it cloud also have been too anachronistic and a little bit unnerving. Instead, Thimbleweed Park was so lucky to get the Californian rock musician and game composer Steve Kirk, who created a wonderful music score that is full of mystery, suspense and even humour, resulting in an amazingly tight atmosphere. The arrangements are not overly epic, since Kirk makes less use of a full orchestra than a small rock band combo headed by guitar, piano and keyboards, but the music is always very melodic and even in the more sparse moments very entertaining to listen to. The actual sound design was created by Ron Gilbert, David Fox and Elise Kates (who also provides the voice of Delores) and has a lot of very natural background noises that are only noticeable when they stop. The foley track could well have been taken out of the LucasArts sound library of the early 90s, but all noises sound appropriately realistic and sometimes (intentionally) quite funny.

For the background music and sound, Thimbleweed Park did fortunately not go back all the way to the early 1990s or even late 80s – while MIDI music, Adlib bleeping or chiptunes would have been fun, it cloud also have been too anachronistic and a little bit unnerving. Instead, Thimbleweed Park was so lucky to get the Californian rock musician and game composer Steve Kirk, who created a wonderful music score that is full of mystery, suspense and even humour, resulting in an amazingly tight atmosphere. The arrangements are not overly epic, since Kirk makes less use of a full orchestra than a small rock band combo headed by guitar, piano and keyboards, but the music is always very melodic and even in the more sparse moments very entertaining to listen to. The actual sound design was created by Ron Gilbert, David Fox and Elise Kates (who also provides the voice of Delores) and has a lot of very natural background noises that are only noticeable when they stop. The foley track could well have been taken out of the LucasArts sound library of the early 90s, but all noises sound appropriately realistic and sometimes (intentionally) quite funny.

From the perspective of someone like me who has still played the original Lucasfilm Games and LucasArts oeuvres, Thimbleweed Park does everything right and hits all the nostalgic spots like no other game has before in the last 20-odd years. You can feel that this game is not just a moneymaking scheme cashing in on the recent nostalgia wave – this is a real labour of love and it’s absolutely amazing that it was actually possible for the old gang of Ron Gilbert, Gary Winnick and David Fox to get back together after almost 30 years and make what amounts to a new Lucasfilm Games adventure. Even more astonishing is that the game development was fully documented on the Thimbleweed Park Blog and in hours and hours of podcasts released almost weekly when the game was made – something that would never have been done only a decade ago.

From the perspective of someone like me who has still played the original Lucasfilm Games and LucasArts oeuvres, Thimbleweed Park does everything right and hits all the nostalgic spots like no other game has before in the last 20-odd years. You can feel that this game is not just a moneymaking scheme cashing in on the recent nostalgia wave – this is a real labour of love and it’s absolutely amazing that it was actually possible for the old gang of Ron Gilbert, Gary Winnick and David Fox to get back together after almost 30 years and make what amounts to a new Lucasfilm Games adventure. Even more astonishing is that the game development was fully documented on the Thimbleweed Park Blog and in hours and hours of podcasts released almost weekly when the game was made – something that would never have been done only a decade ago.

Thimbleweed Park is LucasArts at its best without LucasArts – the company may be gone, but the classic adventure genre lives, made possible by those who started it all thirty years ago. Will there be a sequel or a new game by Ron Gilbert, Gary Winnick and David Fox? They haven’t ruled it out completely, but it will all depend on how well Thimbleweed Park is going to do in the long run. For this reason alone, I highly recommend buying Thimbleweed Park! It’s not overly expensive with the PC version costing about €20 and the mobile incarnation just €10 and every purchase will most probably help deciding whether those guys are going to make another game someday.

Let’s hope that the signals will be strong.